Gerard de Kamper, University of Pretoria and Isabelle McGinn, University of Pretoria

The paintings of Dutch master Rembrandt van Rijn are displayed in prestigious art galleries in capital cities around the world.

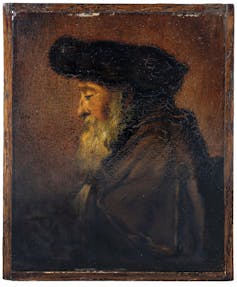

One – a small oil painting on a wood panel depicting the profile of an old man in a hat and cloak – made its way to South Africa in the late 1950s. It was part of an extensive collection belonging to a Dutch businessman, JA van Tilburg, who emigrated to the country. In 1976 the work was donated to the University of Pretoria.

For decades, the work was attributed to Rembrandt, the world famous artist from the Dutch Golden Age of painting (1588-1672). After all, it had a good provenance. Provenance is the study of the history of an object after its creation. Typically in the case of a painting it would be the history of the ownership of the artwork.

The painting was documented as being part of the Warneck Collection, an important private art collection in Paris, as described in the book by Cornelis Hofstede de Groot. But provenance research carried out in the Netherlands in 2015-2016 showed that the painting’s provenance to the Warneck Collection was in fact incorrect.

We work for University of Pretoria Museums and an academic unit called Tangible Heritage Conservation, the only one of its kind in sub-Saharan Africa. Here, over the last three years, we have developed analytical techniques to study the materiality of artworks and objects – all relevant information related to the work’s physical existence, including its history and conservation.

In an effort to get to the bottom of the origins of this particular Rembrandt we started to do provenance research and then started to learn the techniques used in studying the works of Rembrandt on a technical level. In a research paper we concluded that the work previously accepted as a Rembrandt was indeed not by the artist.

The search

We could trace the painting back through 14 buyers and sellers by researching auction catalogues at the RKD (Netherlands Institute for Art History). The painting could be tracked all the way to 1899, when it was described as “surely authentic” by De Groot.

Several factors made us believe the painting might be original. Distinctive marks on the back of the frame, mention of an invoice in Rembrandt’s handwriting accompanying the painting at the 1889 auction, as well as expert reviews suggested that it could indeed be a Rembrandt, or at least from his studio. (It was commonplace for a master to have apprentices work in his studio and on his paintings.) There were even references to chemical analyses of the painting in 1941 by one of the time’s most eminent and earliest technical art analysis scientists, AM de Wild.

But, to determine whether the painting was in fact by Rembrandt, provenance research was not enough. It needed to be complemented by an art historical connoisseurship, which looks at a stylistic review. Are things like the style, colours and composition of the painting typical of the artist’s work? It needed to be backed up by physical evidence through technical art analysis.

Technical art analysis is not widely available in South Africa and there were challenges in taking the painting to Europe to be authenticated. The solution was to start developing local expertise. This included learning to use and understand techniques such as X-ray fluorescence, ultraviolet light and infrared photography to inspect the painting.

Using cutting edge technology we searched for fresh evidence about the painting’s authenticity.

The evidence

Authentication requires multiple steps to ensure all aspects of the painting point to the creator of the work. Photographs taken under ultraviolet light investigated possible retouching and restoration. Infrared imaging techniques looked for any under-drawings or compositional changes. X-rays identified structural components of how the panel was secured in its cradle – and the presence of a lead-based underground to prepare the panel, as well as lead white in the paint.

The wood panel was examined using dendrochronology, a method to date wood down to the year that the tree was cut down, in this case in the 1640s. An analysis of the individual pigments in the painting was also done using a handheld X-ray fluorescence spectrometer.

All the results suggested that the correct elements were present in the painting, specifically lead, to place it in the 1600s, the time of Rembrandt.

Read more: There’s been a spike in fake African art. What’s being done to fight it

But then the opportunity arose to bring in an X-ray fluorescence scanner, which combines X-ray fluorescence sampling with scanning technology. This can help determine the elemental composition of materials. The scanner allowed us to map the entire surface of the artwork, instead of relying solely on a handful of small areas to identify and characterise certain pigments – as was done using the handheld spectrometer.

Now data could be analysed in layers, allowing for layers to be selected or removed from the digital map in order to look at the elemental distribution over the entire surface. A desktop scanner was sufficient in the case of this small painting but the technology is the same as that used at the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam in their Rembrandt Operation Night Watch project.

Although the scanning picked up the same elements consistent with Rembrandt’s palette, these were in minimal quantities compared to what was expected and has been identified in other Rembrandt paintings around the world. Lead white should have been used in the preparatory ground layers and in the white paint, but only minimal quantities were present.

Zinc white was also present. This is problematic as it was only introduced as a pigment in 1834. In addition barium sulphate was found in large quantities. But mining of barium sulphate was only possible from the 1850s onwards.

The outcome

Thus, a creation date is only possible after 1850 when barium sulphate was introduced. This painting in the collection was thus made 200 years after Rembrandt. It remains unattributed.

Several collections in South Africa contain old master paintings like this one. The attribution and age of these works when donated or purchased are simply believed, due to the lack of expertise in art authentication and the cost of sending them to Europe to be authenticated. Proving that these works are not what they seem is likely to become more common.

Gerard de Kamper, Chief Curator Collections, lecturer, PhD candidate, University of Pretoria and Isabelle McGinn, Lecturer and conservator, University of Pretoria

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.